The co-op consultancy

Mar 2015

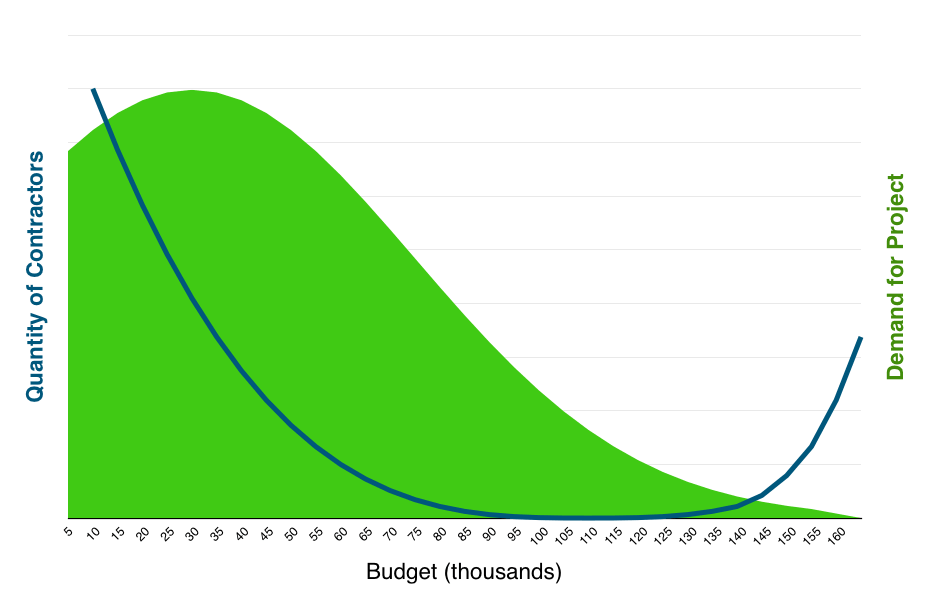

*Fig. A: Contract software development market saturation (ballpark), by job size.*

*Fig. A: Contract software development market saturation (ballpark), by job size.*

Here’s what we’re trying to explore:

- I. How the software contracting market works.

- II. Why the software contracting market doesn’t serve clients or developers very well.

- III. What a decent attempt at a software contracting operation would look like.

#Pt. I: How it works

A thought experiment: you’re an expert in your field, and you want to deploy that expertise in a technology product that will solve a unique set of problems for people in your industry. You’re not a web development expert - perhaps you’re in medicine, or finance, or automobile maintenance - but you’re at the top of your game and you want to do it right. What’s the optimal way to embark on your startup adventure?

###How to build a startup product

- Get a technical cofounder to join you. I had a teammate whose mother gave him some well-meaning advice the night before a big race: ‘Michael,’ she told him, ‘you should just try to run a little faster.’ Thanks, mom. It’s a tautology. Obviously you want a technical cofounder to: share risk and workload, take ownership of the product, earn equity instead of cash. It’s not so easy to find somebody to start your company with you, though, so what do you work on in the meantime? Twiddling your thumbs, trying to sell LOIs?1 Founders of tech startups will always exceed the population of technical people to build them, especially since members of the latter population are often also a member of the former, or thinking of becoming one.

- Schlep first.2 If you’re aiming at a data analysis play, for instance, the initial value isn’t in a ‘delightful’ interface or your onboarding/nurture campaign. It’s the business logic that turns meaningless noise into actionable intelligence, and you can make a machine to do that (slowly, painstakingly) in Excel, one client at a time. Of course, the whole point of the offline-first product is to get the customer feedback and, maybe, traction to accomplish option 1 or 3. Excel doesn’t scale.

- Contract an MVP.3 If you need traction to attract potential cofounders and investors, it often makes sense to build the cheapest thing to get that initial momentum. Who can build your minimum viable product? Outsourcing at this level is dominated by the vast ocean of Elance-oDesk freelancers working for a few hundred or a few thousand dollars per job. Or maybe you’ve just retired from your partner-level position at an investment bank, in which case a different option is available to you (see fig. A above).

###The software builder market

US software consultancies cater mostly to the corporate market, where it makes sense to charge two or three hundred dollars an hour. (For perspective, that means two devs, a designer, and a PM for a month can cost up to $150k. Hiring the same group full-time at an average salary of $80k/yr would run you a little over $26k for the same month.) We’re going to ignore the corporate market because price isn’t really a deciding point for them. They’re not trying to minimize cost, they’re trying to minimize risk.

The quantity of firms dips drastically at the middle of the market for the same reason that the small business market is such a tough nut to crack for startups. It’s a sales dead zone, where the product is complex enough to require an expensive sales cycle but not profitable enough to justify such an effort.

But does demand for software projects actually fall off a cliff between the 20k and 100k price point? I’m willing to bet it doesn’t. Any startup presenting a novel process with technology, rather than creating novel technology, will develop an initial product that does four things: create, read, update, and destroy records. How many types of records are involved doesn’t scale the complexity of the application by much. The only unsolved problem is generally the view logic that combines and presents these actions in a way that’s relevant to the business context. My daily rate would put most robust MVPs right smack in the middle of that range.

In the analogy of selling to small businesses, the degree to which America’s mom-and-pop operations desperately need modern business tools has no correlation with quantity of competition selling to them. (I should know, I spent an educational summer trying to sell to that market for a startup outside of San Francisco.) There is a huge middle class of startups and enterprises who desperately need web application development. It’s the economic needs of contracting firms, not their customers, that shape the market this way.

#Pt. II: Why it sucks

Back to you, our hypothetical expert-cum-founder. Like many new entrants, you’ve decided to open door number 3, because at least this way you’ll have something to show people when you talk about your startup.

After asking around and browsing the market, you realize that the overwhelming majority of software freelancers are concentrated into a few huge bazaars, and post some RFPs.4 Here’s where you roll the dice: you pick any one of a dozen contractors with impeccable ratings to finally build your baby.

*Fig. B: MVP doesn’t mean giving up attention to detail.*

*Fig. B: MVP doesn’t mean giving up attention to detail.*

But you’ve been meticulously constructing this application inside your head for months. What are the chances that the first freelancer you hire is going to build exactly your baby, and not some misinterpreted mutant version of it, as on the right side of Fig. B? Without needing to go hire some designers, or other freelancers to fix up the sketchy parts, or, heaven forbid, a PM to manage the whole mess for you? Developers who can reliably deliver whatever you need do exist, but for the non-technical they’re impossible to pick out of a crowd of similarly rated strangers. Even for major tech companies, gauging interview candidates’ true ability is one of the hardest and most hotly debated problems. Should you really need to roll a crit just to have a successful project?5

This is why people with the means to do so choose a consultancy that will minimize the project risk, for a premium. Banks use Sapient, Deloitte, service providers whose enterprise sales operations are excellent. There are whole cottage industries of agencies that are ostensibly contract software development shops, but actually make their money on risk management or exchange rate arbitrage. Code quality is not in their top five selling points.

So perhaps you, the expert, represent a branch of a larger business, or just resigned from managing your boutique hedge fund, and can afford to burn money to overcome the startup cold-start problem.6

In that case, you’re incentivized to look at the top of the market. But code speed and quality don’t necessarily climb with cost. So while you’re purchasing commoditized developer time, most of your money is actually paying for the superstructure of PMs, design thinkers, social media managers, Aeron chairs, and associated detritus that accumulates around any money-making tech enterprise. In exchange for minimizing your project risk, you’re forced to swallow lots of stuff you don’t actually want.

In effect, you’re buying a car from a dealership that automatically charges you for all the accessories. What percentage of people walk onto the showroom floor and check off all the options? Yes please, I’d like the self-parking, 4G, Netflix, walnut dash, calf-massaging model. Sure, it exists. People must occasionally buy it. But any dealer that exclusively offered the upsell would lose out on the much larger market below and probably go out of business. So why do consultancies get away with it?

Because their customers have no other options. Any project between 20k and 100k is inexorably forced upwards to accommodate the needs of the consultancy. It doesn’t take an economist to see that there’s a better way.

###The problem

Nobody wins as a result of this polarization in the market. Customers are forced to pick between a rolling the dice at the bottom or shelling out for the high rollers at the top, and developers everywhere are busy making money for somebody else. (See the next essay in the series for more on this topic.)

So any solution must deliver quality without extorting clients.

#Pt. III: What would be better

What’s the optimal way to solve the problem you’re still facing as the hypothetical expert/founder? How can the system work better for clients and for developers? If we didn’t know anything about software contracting, what would our solution look like?

###The co-op consultancy

Consultancy owners will tell you that if you want it built right, you don’t have anywhere else to go. And nine times out of ten, they’re right. Having experienced the various perversions of this market firsthand, we decided we’re going to take a shot at fixing it. Our first attempt at the solution is a co-op.

Developers, at least to start, are all people we’ve personally worked with or the people they’ve invited. They might live in Boston or Beijing or Irkutsk, but they share a common level of skill and experience - no room for junior devs. Anonymous code reviews for new invitees and a private trust network keep developer quality high.

Profits are distributed directly to developers on a quarterly basis, weighted by dollar-hours contributed. With no accumulation of support detritus, developers can earn more while still offering clients lower rates.

Clients can work directly with co-op management as if it were a normal consultancy. Alternatively, freelancers with their own deal flow can subcontract specialists (e.g. in design or mobile) through the co-op’s trust network and earn commission on the job.

After a project, developers have the chance to include each other within their trust network (would you like to add this person to your iOS short list?). As trust networks grow, possibilities open up to find team members and specialists through second and third-degree connections.

Just like developers’ time, management’s take is hourly instead of a the total leftover profit. A consultancy or freelancer site built to create value for its owners must extract as much profit as it can get away with. But a co-op built to create value for its members can distribute that value on both sides.

After all, what is a company but a group of ad-hoc teams tackling a series of projects together? We just stripped away everything that slowed us down. And as long as we only have the best people on board with us, we can get away with it.

We are uncovering better ways of freelancing by doing it and helping others do it. Through this work we have come to value:

- trust networks over rating systems

- equitable distribution over price competition

- design iteration over spec writing

- ownership over quality control

That is, while we value the items on the right, we value the items on the left more. Check it out below.

If you’ve got comments, leave them on HN: https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=9080630.

Thanks to Kara Bonner, Jared Cosulich, Connor Hood, Shaun Johnson,Michael Liou, and Andrew Rosenblatt for commenting on drafts of this essay.

- ↩

Letter of Intent. http://www.investopedia.com/terms/l/letterofintent.asp

- ↩

The unsexy, arduous work. http://paulgraham.com/schlep.html

- ↩

Minimum Viable Product. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minimum_viable_product

- ↩

Actually, I’ve never seen a software startup benefit from spending really big before launch. Money is a fantastic way to insulate the product from reality until it’s ‘ready’, or in trade parlance, ‘too late’. The cold-start problem: http://andrewchen.co/how-to-solve-the-cold-start-problem-for-social-products/

- ↩

Request For Proposal. http://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/request-for-proposal.asp

- ↩

Critical Hit. http://www.dandwiki.com/wiki/CriticalHit_Table(4e_Variant_Rule)