What's the big deal, Apple? (with sketches)

Feb 2016

Apple’s been asked to unlock the iPhone of a convicted criminal - a terrorist, no less - and they’ve said no. This seems like a strange decision, and yet everybody in technology treats it as a given that Apple is right. What gives?

We’ll explore:

- why and how iPhones are encrypted

- what the FBI is asking

- why Apple is refusing

##Why new iPhones are encrypted

It’s a dangerous world out there. How many stories air on the six o’clock news each month about a department store losing customers’ credit card information? Internet-connected systems have become almost impossible to protect - there are vast resources being thrown at attacking them. To make matters worse, no matter how much work is put into defense, it’s always possible for a user to click a link in a phony email or shady ad, enter some information, and have unknowingly given the attacker complete access (this is how most malicious hacks happen these days).

Meanwhile, Apple’s encouraging you to put your entire life - and access to your bank accounts and credit cards - into your iPhone. It’s quite forward-looking and responsible of them to build the ultimate defense right into the operating system: encryption. That means scrambling your private information so that, if somebody stole your iPhone and plugged directly into its hard drive, they’d just see meaningless zeroes and ones. Peace of mind, even if you’ve lost your phone. (And even better, Apple’s not legally liable for your ruined life - as big-box stores are often ordered to pay for negligence when their unencrypted customer data is stolen.)

##How iPhone Encryption Works

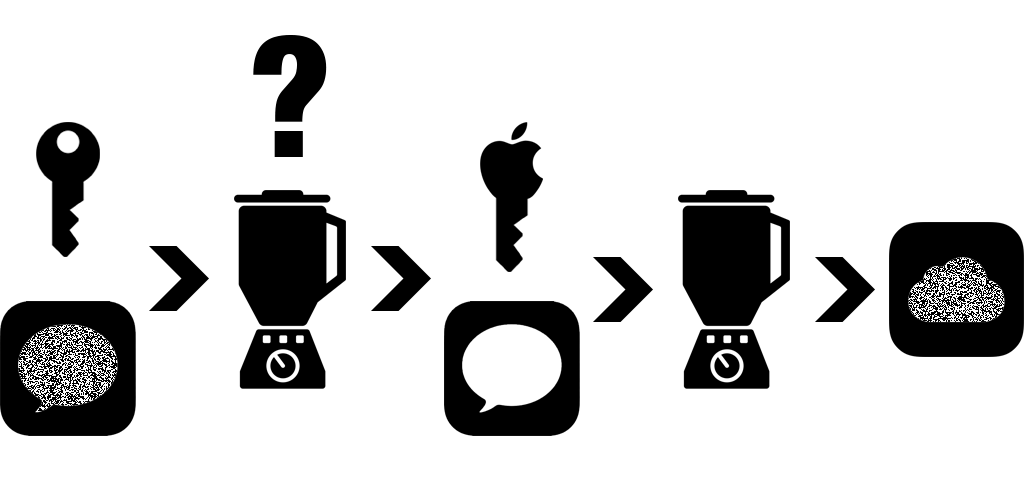

Encryption can be thought of as a blender. Drop in a file, punch in your settings, and it’s transformed into an unrecognizable mess of its former self. What makes it useful is that it can be run in reverse - punch in the identical settings, run the blender backwards, and voila, your encrypted smoothie has been reassembled into its constituent ice cubes and fruit. How these blenders work is public information (and mathematicians are constantly competing to make them blend better), so the key is knowing the settings.

*Fig. A: Your data, together with your unique key, get scrambled on your iPhone’s storage.*

Your iPhone is your fortress. Whether you use a passcode, a fingerprint, or something else, your key represents your personal blender settings. Nobody without that key, not even Apple, can reconstruct your information. This is why the phone will lock you out after too many wrong guesses. It’s why iOS makes it so hard to blindly guess a passcode, even with a machine guessing really fast - an iPhone takes some time to try each guess, making it ineffective to build a machine that will guess an infinite number of combinations (called a brute-force attack). And it’s why their support page for lost passcodes is just a set of instructions for how to wipe your device and start over from a backup.

But where does that backup come from? Apple, naturally. You’ve got an iCloud account, and before your iPhone backs up to iCloud, you’re actually unlocking your device, decrypting everything so Apple can see it. You enter your iCloud password to confirm who you are, and then Apple vacuums up your info - and encrypts it again, of course, this time with their key.

*Fig. B: In the right conditions (a home wifi network and a remembered iCloud password), your data is automatically decrypted so that Apple can re-encrypt with their own key it as an iCloud backup.*

##The FBI’s order: fight terrorism by any means necessary

The police can come to Apple with a warrant, and they’ll decrypt the iCloud backup of your phone and hand it over immediately. This happens all the time. They actually did it in the San Bernardino case and recovered the most recent iCloud backup from a few weeks before the shooting. But incredibly, the FBI told the San Bernardino police department to reset the phone’s iCloud password. They did, effectively making sure the phone wouldn’t sync to iCloud until the phone’s passcode was entered.

This brings us up to date with the case - the FBI took possession of a terrorist’s work phone (not their personal phone) with a few weeks of encrypted iMessages. Nobody can read the encrypted data, and they can’t guess the encryption key. They couldn’t even plug a brute-force machine into the phone that would make it think an infinite list of passcodes were being entered really, really fast - iOS is too smart for that. (If it wasn’t, any thief could plug a homemade box into your phone for a few seconds and steal everything you’ve got.)

*Fig. C: By resetting the phone’s iCloud password, the authorities prevented the phone from automatically syncing with iCloud - decrypting the phone’s contents - again.*

So with the regular iCloud warrant no longer an option, the FBI ordered Apple to create a new version of iOS - a version they can swap in for the secure version, that will let them run a brute-force attack until they guess the right passcode and decrypt the last few weeks of data. They didn’t really need to ask: anybody can write a bootleg version of iOS, just ask a friend with an ‘jailbroken’ iPhone. The protections that stop you from downloading extra apps that aren’t on the App Store are part of the very same software that stops attackers from brute-forcing your passcode. And if teenage coders can jailbreak a phone and install a different version of iOS for fun, can’t the FBI do it for national security?

Of course they can - and lose the suspect’s private information along the way. iPhones are built so they can’t upgrade to any iOS release that didn’t come directly from Apple. They need to be ‘reformatted’ to update a bootleg version, losing their data in the process. The difference between a bootleg version and the official iOS is that Apple signs official iOS releases. What are they signed with? You guessed it, Apple’s own key. Their private settings to the encryption blender. So the FBI - relying somewhat tenuously on the All Writs Act of 1789 - has ordered Apple to develop and hand over a version of iOS with no protection against brute-force passcode attacks, and then to sign it so that all iPhones will implicitly trust it.

##Apple’s response: One Key to rule them all

This is something Apple has never been asked to do before. Probably no tech company has been asked, yet - even telecoms building special rooms into their infrastructure for government interception retained control over those rooms, making sure that only the NSA would be able to take advantage of them. In contrast, this key would enable anyone who holds it to crack iPhones at will. Apple published a defiant refusal not because they felt like a publicity stunt, but because an intentionally vulnerable release of iOS would put every iPhone owner in the world at risk. (Technically they could limit the damage to just the iPhone 8, because of how they sign releases, but in their view that’s beside the point.) Once released, it would be a master key to for anyone holding it to bypass the work Apple has done protecting their customers.

The master key to iPhones is only a problem if it falls into the wrong hands. What if the FBI just used it for this one case, the San Bernardino case, and then deleted it? What if Apple could help the FBI fight terrorism without exposing the rest of their customers?

##The real question

The FBI is promising that exact compromise. They have a tough job on their hands, protecting America from homegrown terrorist attacks in a strange new century. To accomplish that job they’ll use all the tools they can get, including any tools they can order private companies to create. The true question Tim Cook faces: does he trust the US government?

The agents who naively ordered the suspect’s iCloud password to be reset, starting this whole debacle - does Tim Cook trust them with the safety of the master key? That it won’t be lost, copied, or stolen, that they’ll delete it when they’re finished? If not, the software will eventually get out, and he’s given his users to criminals and foreign governments.

The police commissioner of the NYPD has already described the hundreds of iPhones he would like unlocked - does Tim Cook trust that the FBI would turn down the NYPD and every other state and city agency clamoring for this key? If not, the software will eventually get out, and he’s given his users to criminals and foreign governments.

And even the government itself - the FBI that sent secret death threats to Martin Luther King and sent people to prison with fake bullet analysis for 40 years, that botched its own investigation in the San Bernardino case, and now demands Tim Cook expose his customers - should he create the One Key for this group? Is he legally required to create it? And does he believe them when they say its application will be limited?

He says no. He says that the All Writs Act obliges him to turn over data, not to develop a brand new iOS. He says if the FBI had been competent in the first place, Apple could have helped them with a regular iCloud warrant and they wouldn’t face this problem. He says that, like the One Ring of Tolkein, the key being requested is evil by nature: its only purpose is to expose millions of his customers to the potentially unlimited number of unknown people who will inevitably wield it. And having created it, there will be no going back: he’ll have set the legal precedent for all US tech companies to create security holes exposing their users. Those holes will be exploited by everyone - by the US government, by criminals, and by foreign governments. He says we’re safer in a world where we can keep our own secrets than in a world where there are no secrets.

Now it’s up to the courts to decide if he’s right, and maybe up to Congress to create new authority for the FBI. What a show that will be, if they ever get around to it.

Image credit:

- Blender by Ale Estrada from the Noun Project

- Key by John Caserta from the Noun Project